4 Stages of Writing a Sonnet

How do you write a sonnet? Here are 4(ish) easy steps to wrestle one to the ground and strap it into its car seat like a wayward toddler.

I went on a sonnet kick recently. As always, I was full of wild ambition and thought I would ask Twitter for prompts, calling it the #dailysonnet. How we all laughed. I think I managed to write about 7 sonnets in total (not sure, I am not great at counting), definitely not one a day, and several lovely prompt-contributors are still waiting for their poem four months later.

To deflect attention from this abject failure, I am here offering up a behind the scenes tour of how my sonnets are written - if indeed they ever do get written. A typical sonnet has 14 lines, arranged in stanzas (can be 4 lines, 4 lines , 3 and 3 or 4 - 4 - 4 - 2), with a ‘volta’ or twist near the end. It rhymes and it has a very strict meter. The meter is called ‘iambic pentameter’, which means you have two syllables that go “te-TUM” and you repeat that five times in a line.

Now that you are an expert like me, let’s write one!

1a. The Prompt

Often I struggle with a poem that is supposed to come explicitly from a prompt. The ones that didn’t come easily were the ones where someone had dropped in a word or phrase at random - that was a lot of pressure and it felt like jumping from standing.

The best prompts come from a conversation - they already have a story. A friend asked me to write about Christ - we ended up talking about politics and he said either Jesus Christ or Dominic Cummings were my ideal sonnet subject. An idea was born (see picture).

(screenshot shared with permission of Dr Gijsbers)

1b. The Concept

As said, a good prompt already contains the concept. But there are things to work out. I had a ‘visual’ connection between DC and JC - a garden - but how was I going to connect them thematically? I made some notes to see if anything suggested itself.

I decided the connection was that both were set up as an example to emulate; but where Jesus did a great job of showing love and compassion, Dominic Cummings failed at this spectacularly.

2. The Rhyme

Do you find rhymes to fit the line or lines to fit the rhyme?

Kind of both. Whichever works best. Years of practice writing St Nicholas Day poems has taught me that you can’t be too precious about your ideas in a rhyming poem. Sometimes you have a great idea for a line but you just cannot make it work with its counterpart, in which case one of them will have to go. Most of the time, this forces you to come up with something even better.

I will fill the page with rhyme words before I start and during writing, and often the process of coming up with all possible options will suggest unexpected new twists in the sonnet.

3. The Draft

Armed with ideas and rhyme words, it is time to try and wrestle the words into iambic pentameter and stanzas and try to work in a volta. And it really does feel like wrestling. A bit like folding the four flaps of a box down - when you have three of them sorted the fourth one pings up and hits you in the chin.

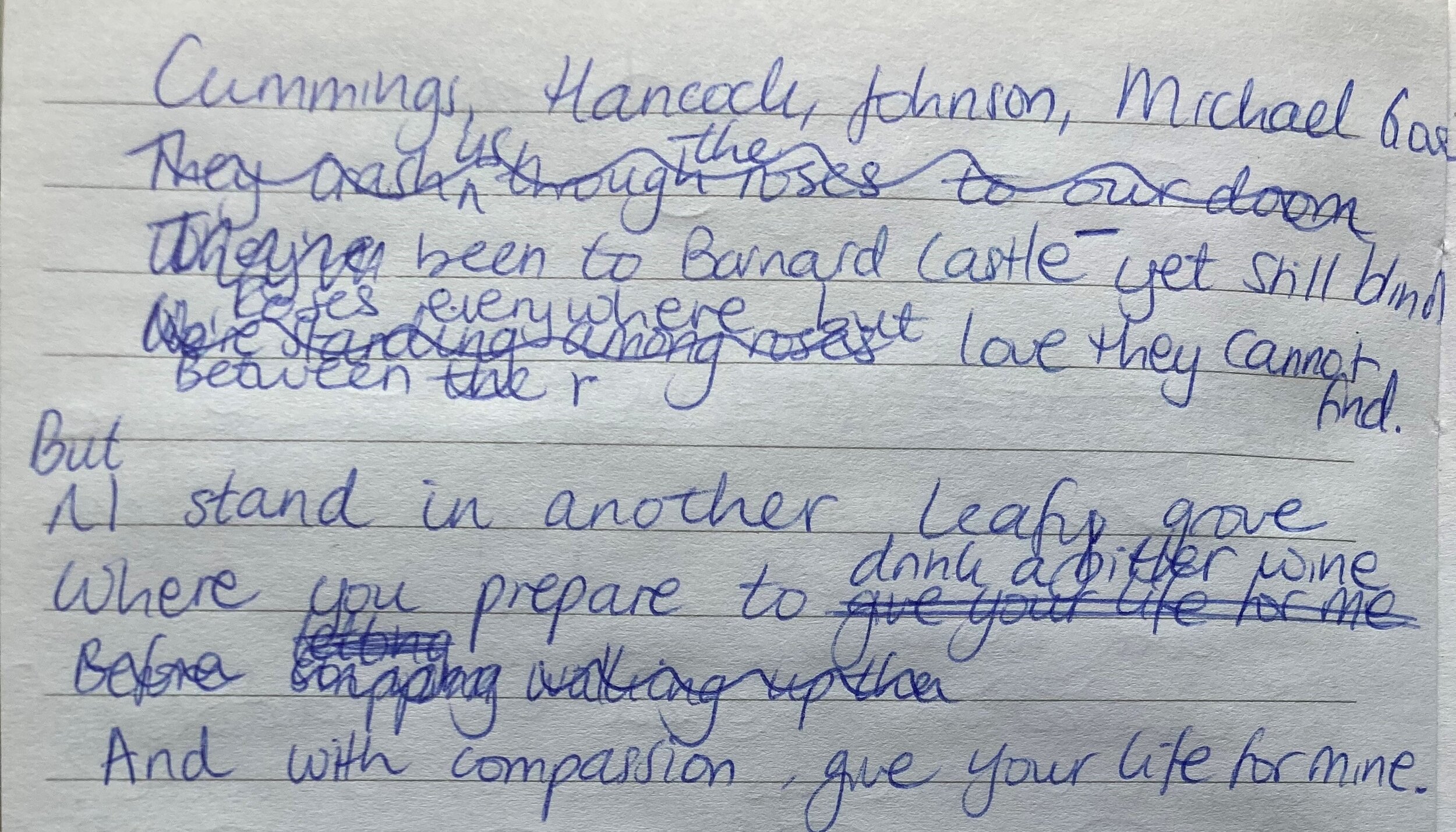

While drafting, I do a lot of whispering. “Te-tum-te-tum-te-tum-te-tum-te-TUM". You can see in the picture how many lines I have to reject in order to make the stanzas work as a whole.

The draft is done when I have got 14 lines, they mostly scan and I feel a stir of excitement when I read it out loud. The this could be good-feeling.

4. The Edit

Once I have a draft, I type the sonnet up in Word. Often, this will immediately lead me to spot issues or make tweaks. In every poem draft, there are words or phrases that bother me, like a stone in my shoe. I find myself frowning every time I read them. Those are the things that need to change.

In a sonnet, I will feel like I have nailed the rhymes in the draft phase, but the meter is something I will keep refining while I edit.

Sometimes it is other people who come with great tweaks that I hadn’t seen. In this one, it was my husband who made the brilliant suggestion that “Cummings, Hancock, Johnson, Michael Gove” would be even better as “Cummings, Hancock, Johnson, Raab and Gove”.

5. The Beginning and the End

The hardest part of anything you write, I find, is how to start and how to finish.

The last line is the one I rewrite the most. A poem (or blog post or story or article or novel) has to ‘land’. The reader needs to know it is finished and feel a sense of closure. I try to find something that sums up the poem, ties it together and preferably provides some kind of lightbulb moment - this can take a while.

The title is just as important. In Theatre Studies, I encountered the idea of “Framing and Preparatory Indicators”. Your arrival at a show sets up how you will experience and interpret it: is it in a theatre or in a warehouse? Who greets you when you come in? What does the waiting area look like? In the same way, the title of a poem will colour every word you read after that and give it additional meaning.

This one started as “Christ” but ended up as “Christ Almighty”. Have a listen below and see how you might read it differently with one title or the other.

Image credit: P.M. Kroonenberg

And that’s it! The sonnet is done! You can listen to the finished version of Christ Almighty here.